The Dangerous NASH Equilibrium in Companies

- Cem Akant

- Jun 9, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 23, 2025

In seasoned companies, everyone tends to do their job well:

· The Sales team focuses on “hitting this month’s targets.”

· Marketing says, “We must protect the brand perception.”

· Finance insists, “Let’s not put cash flow at risk.”

They are all disciplined, data-driven, experienced—and justified from their own perspective.Yet despite this, things feel off. The signs show up in broken communication and, more tellingly, in the company’s medium-term stagnation.

How does this happen?Each player makes the most rational decision for themselves—assuming others won’t change their position. The resulting "equilibrium" is a state where no one can achieve a better outcome by unilaterally shifting strategy. This is what game theory calls the NASH Equilibrium.

In theory, it’s an equilibrium. But in practice, it often produces suboptimal outcomes. Why? Because the players don’t trust each other, can’t align decisions, or the game itself is structurally flawed. So, the system suffers.

Let’s look at real consequences:

- Sales wants to attract buyers with a fast-paced, discounted campaign.

- Marketing fears this erodes the brand’s premium image and opposes the move—often rightfully so.

The result? Conflicting messages reach the customer. The campaign’s impact fizzles out. Sales disappoints. The brand gains nothing.

No team is willing to move first. If the others don’t shift, any unilateral compromise feels like a loss. This isn’t limited to sales and marketing. Take Sales and Finance:

- Sales pursues a big order. It needs flexibility.

- Finance raises red flags: “Cash flow risks, long payment terms.”

In the end, Sales pushes forward. Finance doesn’t budge. The order is placed, but collection becomes a nightmare—or the deal is lost altogether.

Everyone believes they’re right. But the system bleeds.

You see the same in mergers and acquisitions.The acquiring CEO may prioritize personal prestige—picking the scenario that best fits their career narrative.The acquired company, especially in early stages, may play along to cut losses.Consultants? Rather than focusing on post-merger results, they often paint risks with overly optimistic tones—motivated by their own incentives. The real goal? To tell a great-sounding strategy story.

(One of my favorite lines, often attributed to Churchill, comes to mind:"No matter how beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.")

And so, many mergers fall far short of their promised value.

What’s the way out?Leadership’s job is not to find who’s “right”—but to change the game itself.

Let’s bring this to life with a realistic scenario:We're in a tech company. Classic case: Everyone is under performance pressure.

Different departments voice their concerns:

· Sales: “Let’s hit the market hard with this product—it’s overpriced at the competition. Volume is our goal.”

· Marketing: “This will damage our premium image. We don’t have the budget for a campaign like this. That price won’t fly in our target segment.”

· Finance: “Margins are thin. Let’s not strain our already tight cash flow.”

· Production: “Why are we pushing Product X and not Y? We invested in Y. We need volume. X has lower margins and makes our factory look inefficient.”

All valid points.Everyone’s chasing their KPIs.No one wants to be labeled the “problem department” at the next board meeting.

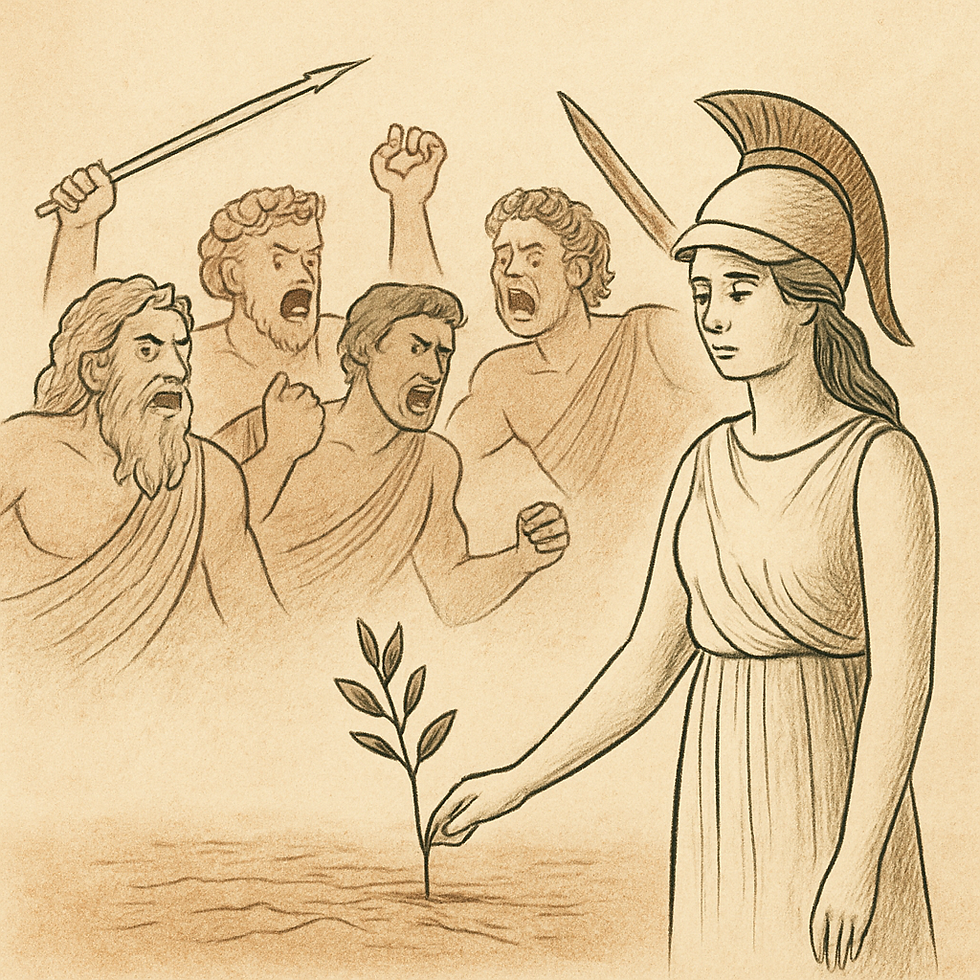

The result?Defensive postures. Lost opportunities.As this pattern repeats, it morphs into what’s known as a Mexican Standoff or Deadlock.

Four players pointing guns at each other—No one fires the first shot. Because whoever moves first believes they will lose the most.

In corporate terms?

· Everyone digs into their position.

· No one wants to take the first hit.

· Everyone avoids loss, but the system slowly erodes.

· And most dangerously, internal trust collapses.

The good news?This negative equilibrium can be broken—by changing the rules.

That’s where RGM (Revenue Growth Management) comes in. Not just a mediator—but a game designer.

RGM builds shared strategy across the company.

What does it do?

· Balances sales, pricing, promotions, margin, and category management.

· Brings department priorities into one clear picture—enabling scenario-based, data-driven decisions.

· Doesn’t just mediate between “discount vs. prestige” or “sales vs. sustainability”—it reframes the whole question.

The outcome? Each player no longer focuses only on their next move …they start seeing the entire game.

How does the NASH equilibrium emerge in mergers?

On paper, mergers often appear “logical.” However, if both parties try to justify their own positions, the system cannot move forward. If the parties are relatively equal in size, the NASH equilibrium becomes even deeper.

Each party chooses what seems the most rational for itself, assuming the other will not change its stance. But when these choices combine, they may fail to create overall value.

For example, one side takes the lead through its processes, while the other tries to assert influence through profitability. The result? → A hybrid structure, difficult leadership dynamics, and delayed integration.

Consultants usually work with good intentions. However, if both sides are too eager to merge, team projections may become overly optimistic. In such cases, consultants’ reflex to challenge weakens. The hard questions are postponed. And the synergy potential remains untapped.

So, how can we fix it?

Strategic Reality Instead of Artificial SymmetryClarify which party is stronger in which areas before starting the decision process:

Process discipline?

Market adaptability?

Human capital?

Allocation Based on Metrics, Not RolesInstead of asking “Which company will provide the CEO and key roles?”,we should openly and early ask:

“Which side will be responsible for which performance metric?”For example:

Who drives operational efficiency?

Who leads innovation?

Who manages channel expansion?

Establish a Shared Value Map with RGM From the Start

In which segments will we grow?

Which categories will be prioritized?

How will decisions like margin, investment, and discount be distributed?All of these strategic choices should be modeled from the beginning using an RGM (Revenue Growth Management) approach.

Owner of Integration: An Internal, Neutral, and Empowered TeamConsultants bring vision, but there may be pressure to create overly positive scenarios. Therefore, an internal yet neutral structure should lead integration and be effective not only operationally but also strategically:

Monitoring KPIs

Tracking cultural alignment

Making decision-making processes more objective

Addressing goal deviations

Identifying new opportunities

Redesigning the structure when necessary

In short, the NASH equilibrium may rarely be visible in mergers — but its effect is powerful. The parties may be well-intentioned. The consultants may be solution-focused. But if the “right structure” is not built, the process runs not on goodwill but on assumptions. And if those assumptions go unchallenged… no value is created.

Comments